Pathways to stability

Best practices on securing land tenure for urban displaced communities in Somalia

Unravelling Housing, Land, and Property challenges in Somalia

The Somali people have a deep and long-standing connection with the land, which has sustained their lives and livelihoods for generations.

Despite this close relationship, the country has limited legal and policy frameworks around Housing, Land, and Property Rights (HLP) and inadequate and non-functional land management systems.

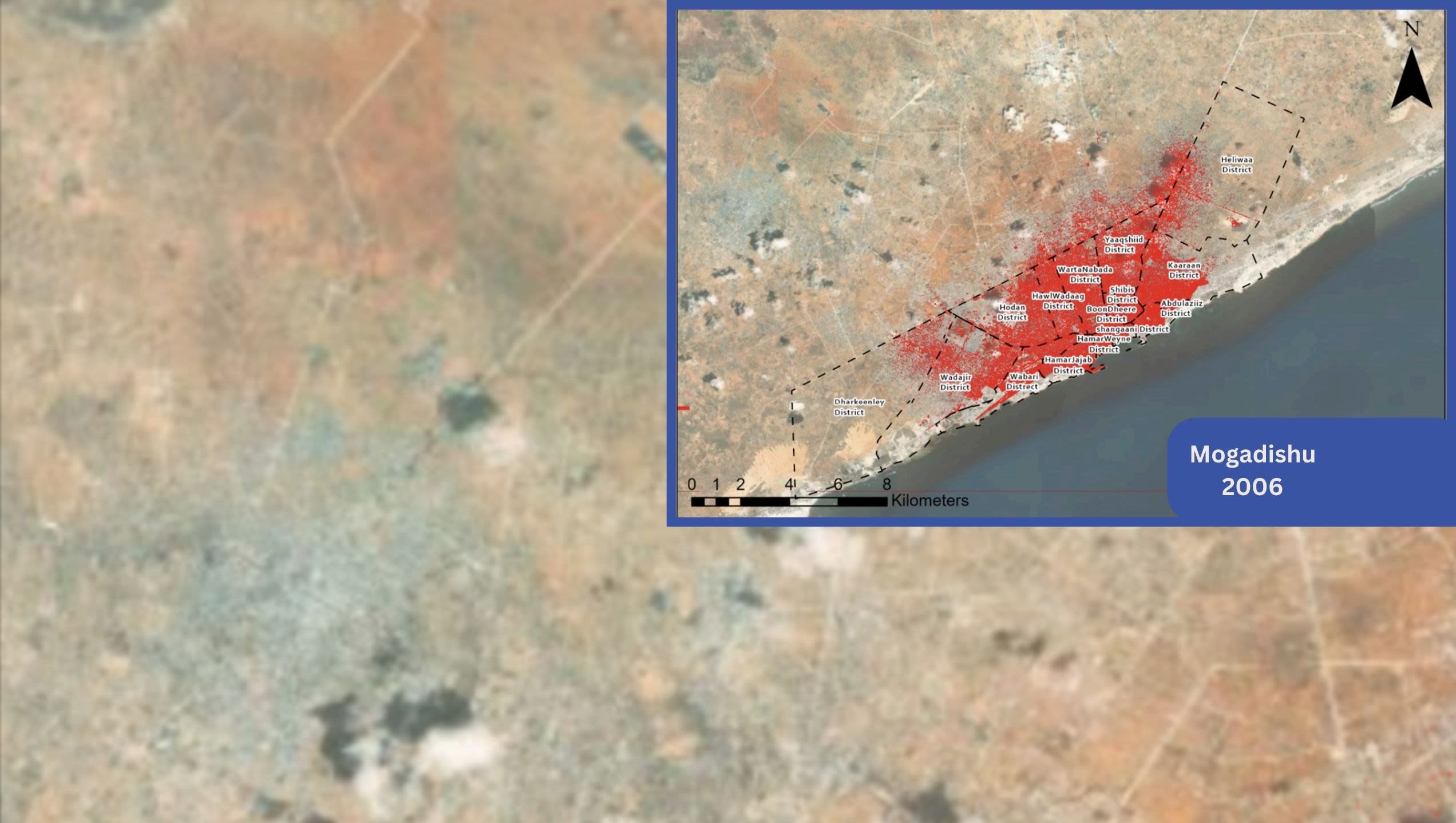

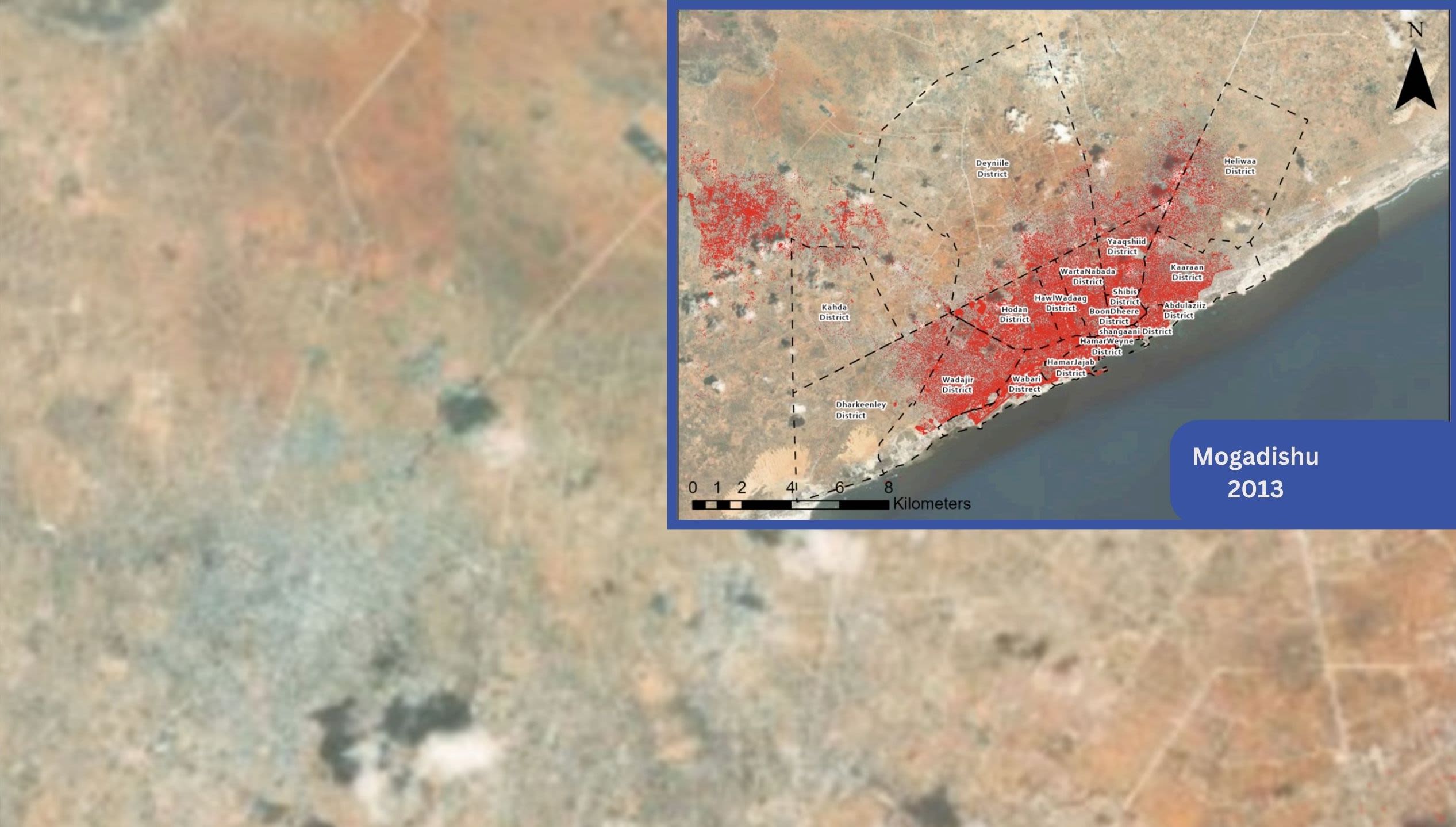

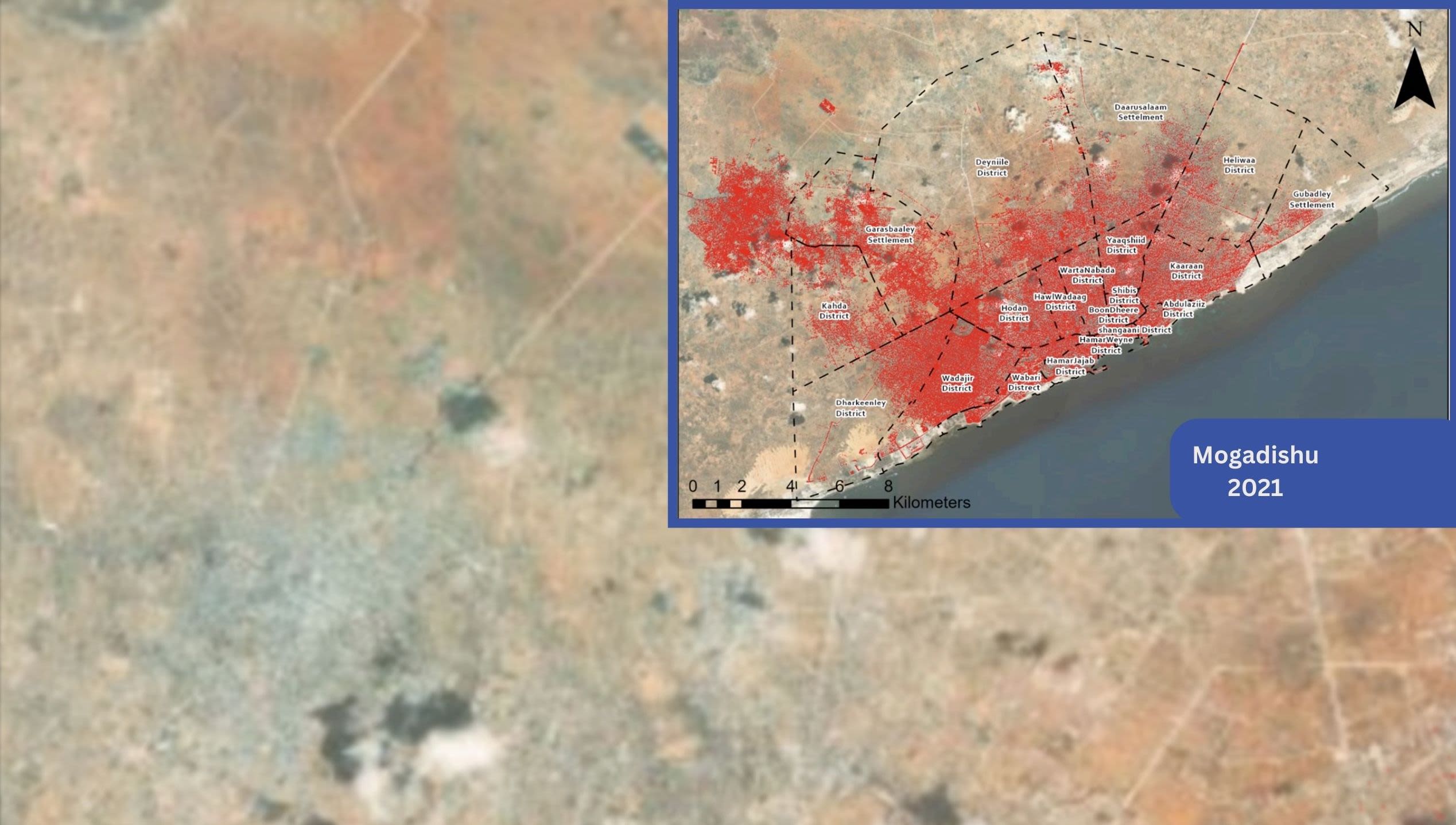

In recent years, Somali cities have undergone rapid urbanisation, as captured vividly in these maps showcasing the sprawling growth of Mogadishu.

This phenomenon, fuelled by factors such as drought, insecurity, and poverty-induced forced displacement, has unleashed unprecedented demand for land in both urban and peri-urban areas.

However, the land sought remains largely under the ownership of absentee landlords, lying dormant and contributing to artificial land scarcity. Lack of comprehensive and reliable land inventory has led to rise in conflicting claims and fraudulent titles, causing more frequent and increasingly severe land disputes.

These factors, combined with rampant land speculation, have pushed land prices beyond the reach of the majority, making land ownership unattainable for most.

As a result, a significant portion of Somalia’s urban population is housed in informal settlements, of which 85% occupy privately-owned land without legal guarantees, documentation, or rights. In instances where tenure agreements do exist, they often take the form of informal “gentlemen’s agreements” that can be easily violated, altered or invalidated without prior notice. This precarious situation perpetuates uncertainty, leaving tenants vulnerable without the protection of legally recognised tenancy rights.

Aerial view of Medina IDP site in Kismayo. Foresight/ IOM 2020.

Aerial view of Medina IDP site in Kismayo. Foresight/ IOM 2020.

Aerial view of informal settlements in Mogadishu. Ismail Abdihakim/ IOM 2021.

Aerial view of informal settlements in Mogadishu. Ismail Abdihakim/ IOM 2021.

As urbanisation continues to reshape the landscape, profound changes in land use patterns are emerging. Land grabbing, contested and multiple land claims, illegal occupation and squatting, unauthorised land sales, repurposing of land, urban development and infrastructure projects as well as government interventions affecting property market dynamics form a complex web and place a host of pressures on land.

Collectively, these dynamics

—which exist between parties of disparate power levels—

lead to widespread forced evictions.

Displaced and destabilised

Exploring the widespread impact of forced evictions

Forced evictions are akin to forced displacement caused by other, more “traditional” crises like droughts, floods, conflict and political instability.

An elderly woman in front of her newly constructed makeshift shelters at the Dambal Caalam IDP camp in Baidoa. IOM/ 2022.

An elderly woman in front of her newly constructed makeshift shelters at the Dambal Caalam IDP camp in Baidoa. IOM/ 2022.

This unrelenting practice leaves families without homes and land and thrusts them into the depth of extreme poverty and destitution, stripping them of their dignity and compromising their physical safety. Evictions exacerbate pre-existing inequalities, disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable and marginalised in the society, including women, children, minorities, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

Children accompany their parents as they arrive in a new IDP settlement in Baidoa. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2022.

Children accompany their parents as they arrive in a new IDP settlement in Baidoa. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2022.

Women and girls often become targets of physical and sexual violence following evictions, particularly if they fail to secure immediate relocation. Additionally, forced evictions can have severely detrimental effects on children's emotional well-being and sense of stability.

Compounding displacement woes

How forced evictions amplify existing challenges

Internally displaced persons are especially vulnerable to and affected by forced evictions.

Of the 3.8 million Somalis who are already internally displaced, over 70% now live in urban and peri-urban centres, where they primarily reside in unplanned, spontaneous, and chaotic IDP settlements that have mostly sprung up illegally on privately-owned land.

These displacement sites are often densely populated and characterised by precarious makeshift shelters, inadequate sanitation facilities, and limited access to essential health care, which expose the residents to a multitude of health and physical security risks. The absence of secure and documented land tenure and lease agreements leave the displaced vulnerable to eviction.

This young woman was displaced from her home due to drought. Ismail Salad Osman/ IOM 2022.

This young woman was displaced from her home due to drought. Ismail Salad Osman/ IOM 2022.

Forced evictions are traumatic for the internally displaced. They force already vulnerable people to start afresh, violate their human rights, and destroy humanitarian and community investments.

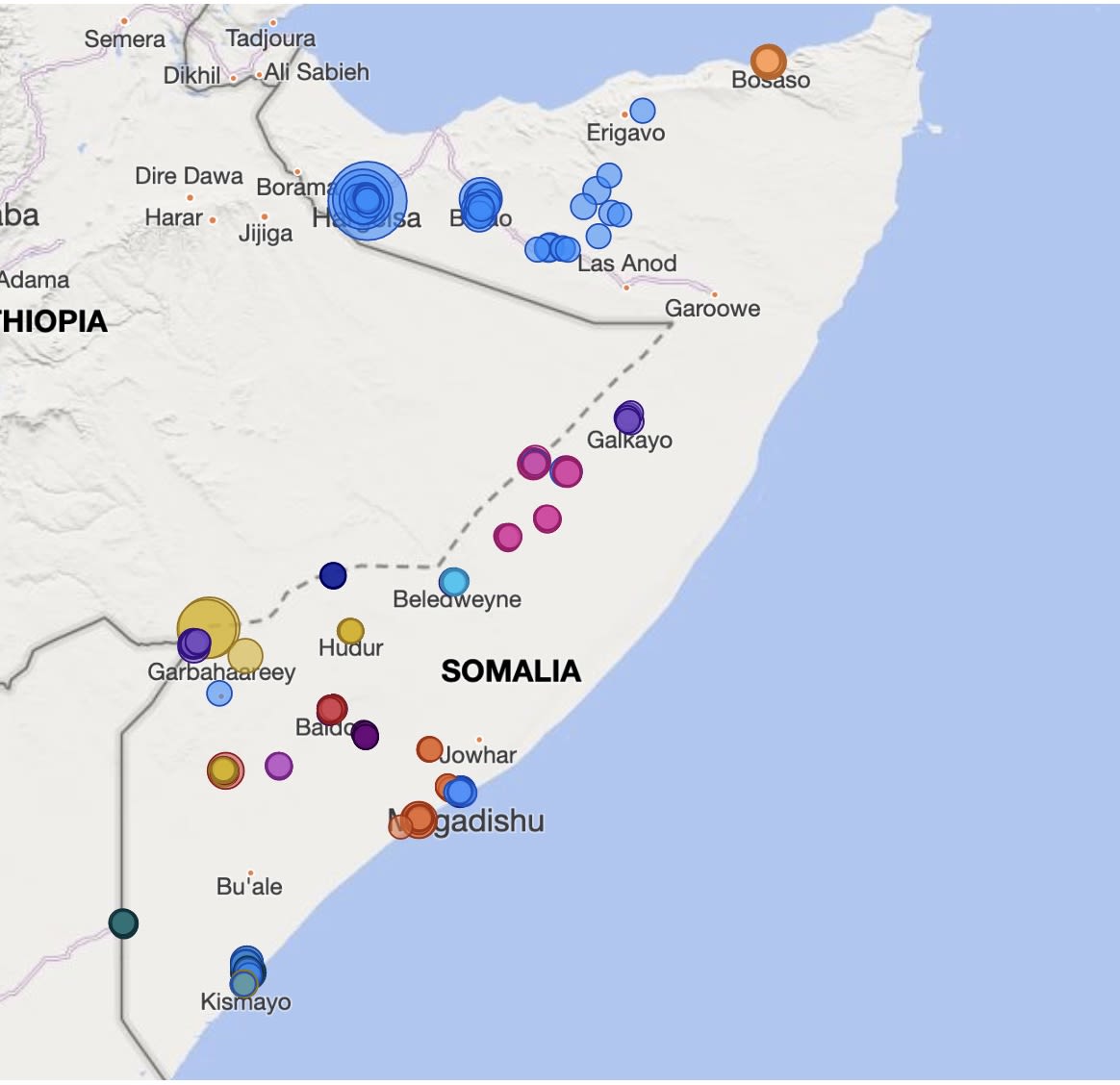

IDP settlements in Somalia are predominantly concentrated in and around urban centres, as shown in the CCCM Site Monitoring Dashboard.

IDP settlements in Somalia are predominantly concentrated in and around urban centres, as shown in the CCCM Site Monitoring Dashboard.

The internally displaced have already uprooted their lives once, twice, or even more times throughout the years.

A comprehensive 2021 study on the social and health impacts of forced evictions on displaced persons revealed that beyond the physical health challenges from high populations and unsanitary living conditions, those evicted also suffer from heightened stress, anxiety, psychological distress and trauma.

Importantly, because of the way in which displacement sites are formed, and later, managed, tenure arrangements are often communal between a landowner and the displaced community. Unlike individual lease arrangements, where displacement sites are concerned, a rupture with or end to a communal land tenure agreement can result in the removal of hundreds of individuals and families or an entire community.

Impact on communities and the humanitarian sector

The effects of evictions extend beyond the families and individuals directly affected; they impact the entire humanitarian and community infrastructure built to support them.

A recent loss and damage cost analysis from NRC found that in 2022 alone, the humanitarian sector and local communities in Somalia lost over US$4.6 million in infrastructure and investments due to forced evictions, which were mostly caused by insecure land tenure.

This included the destruction of latrines, water tanks, shallow wells, community centres, schools, health centres and solar lights and ultimately undermined access to critical essential services such as water, sanitation, nutrition, health, housing, and education.

Forced evictions undo any progress towards achieving sustainable and lasting solutions from both a humanitarian and development standpoint, resetting any incremental gains.

Unveiling the obstacles:

Somali women's limited access to Housing, Land and Property

In Somalia, women possess formal legal protections for their housing, land, and property rights, as established by a combination of statutory, customary, and Islamic laws. However, the practical realisation of these rights often encounters significant obstacles.

Women's access to their HLP rights is frequently mediated through male relatives, and entrenched patriarchal traditions and cultural norms prevalent in Somali society perpetuate a cycle of chronic poverty that hinders women from asserting their rightful claims.

They therefore encounter difficulties in resolving disputes and seeking justice when their HLP rights are denied, leaving them vulnerable to eviction and exploitation.

Halima's story

Halima is a single mother of eight who was an agro-pastoralist in Burhakabo, in the Bay region of Somalia. In 2021, her life took a devastating turn when the severe drought in the country killed hundreds of her cattle. Desperate for survival, Halima and her family fled to the outskirts of Mogadishu in search of food, water and humanitarian assistance.

Like many other internally displaced persons who had lost everything, Halima found materials to build a makeshift shelter in a displacement site located on privately owned land. Though the conditions were overcrowded and overwhelming, she was grateful for the stability it provided, as her family could access basic needs like water and food as well as education as they attempted to rebuild their shattered lives.

Their newfound hope was short-lived. Within a few months, the landowner abruptly decided to develop the land, subjecting Halima’s family and all of the other displaced people to an eviction. Their make-shift shelters were demolished, leaving them homeless.

“Being forced out and destroying my home was like destroying my life.”

Halima and her children sought refuge in Kalkaal displacement site, also in Mogadishu. However, here they were subjected to yet another eviction. This pattern of being uprooted and displaced repeated itself five times over the course of a single year, leaving Halima and her children in a state of uncertainty, hindering her attempts to rebuild her life, and denying her children access to education.

Throughout these evictions, Halima and her children endured physical violence, constant instability, psychological stress, and deep emotional trauma. In one harrowing instance, a group of armed youth—incentivised by the landowner—stormed Halima’s home, unleashing a wave of violence that destroyed their possessions. Halima manged to escaped with a broken arm but was separated from three of her children amidst the chaos. For days they lived in fear, uncertain if they would reunite. Eventually they found one another, but the terror from their experiences persists, leaving them haunted by fear and anxiety.

Breaking the barriers

Danwadaag's approach to overcoming limited access to housing, land, and property

In this video, Laura Bennison, the Danwadaag Consortium Coordinator, shares how HLP fits in the programme's approach.

In this video, Laura Bennison, the Danwadaag Consortium Coordinator, shares how HLP fits in the programme's approach.

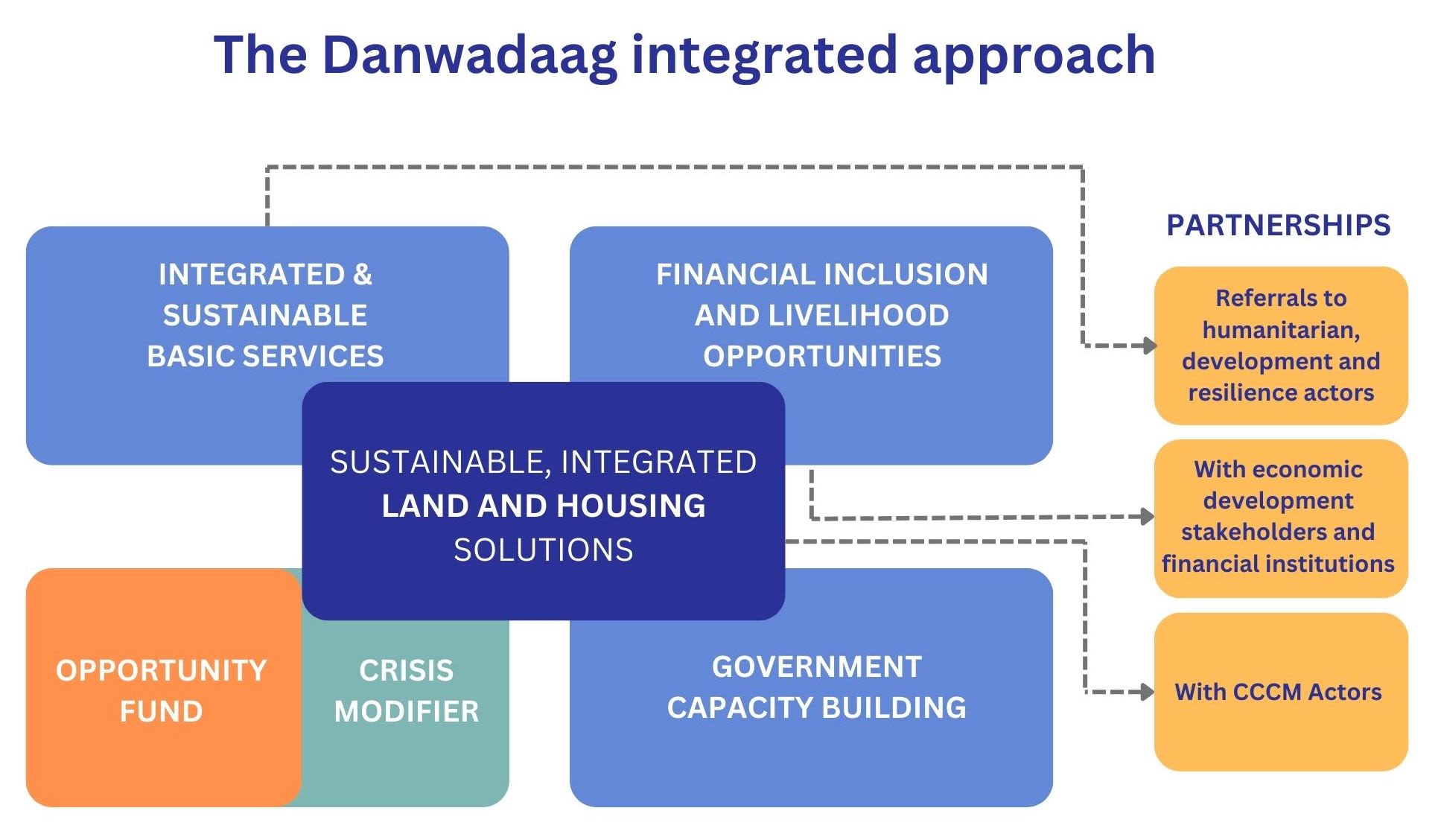

Since 2018, the Danwadaag Durable Solutions Consortium has been working to enhance durable solutions for and (re)integration of displacement-affected communities in Somalia by supporting government capacity building, delivering integrated sustainable basic services, empowering communities to claim their HLP rights, enhancing land tenure security, and promoting sustainable livelihoods. Danwadaag works in key urban centres across South West State, Banadir Regional Administration, Jubaland and Puntland.

Supporting housing, land and property rights—in particular, securing land tenure—is at the core of Danwadaag’s approach to creating a supportive environment for lasting solutions to displacement.

Danwadaag’s collaborative approach has allowed the project to reach difficult-to-access areas, establish strong connections with local communities, and bring innovative solutions to address the needs of displaced communities in Somalia to scale. All of Danwadaag’s interventions take a people-centred, bottom-up approach that ensures that the needs of marginalised people are included in planning and design.

The focus of Danwadaag’s housing, land, and property rights work is supporting displaced people and communities to obtain land tenure security, an important pathway for sustainable (re)integration and prevention against forced evictions.

Danwadaag’s work on land tenure security takes a multi-pronged, multi-level approach, shown in the diagram and detailed in the sections below.

Danwaadag has benefitted from the vast experience and leadership of the Norwegian Refugee Council on HLP issues both in country and globally. NRC is the technical lead for HLP issues within the consortium.

Displaced women receive shelter materials in Mogadishu. IOM 2022.

Displaced women receive shelter materials in Mogadishu. IOM 2022.

As one example, Danwadaag provided Halima with free legal aid and relocation support, enabling her to move to a displacement site with a formal, five-year written tenure agreement. Danwadaag also referred Halima to other partners for shelter, education, and psychosocial support.

“I am now living in my shelter, in the new site with a formal agreement that spans five years. My children and I no longer experience the fear of potential forced evictions. We are rebuilding our lives.”

Facilitating government-led relocations

The Barwaqo project in the rapidly-developing city of Baidoa serves as an excellent example of how Danwadaag, in collaboration with government and other actors, has successfully facilitated the relocation of displaced people.

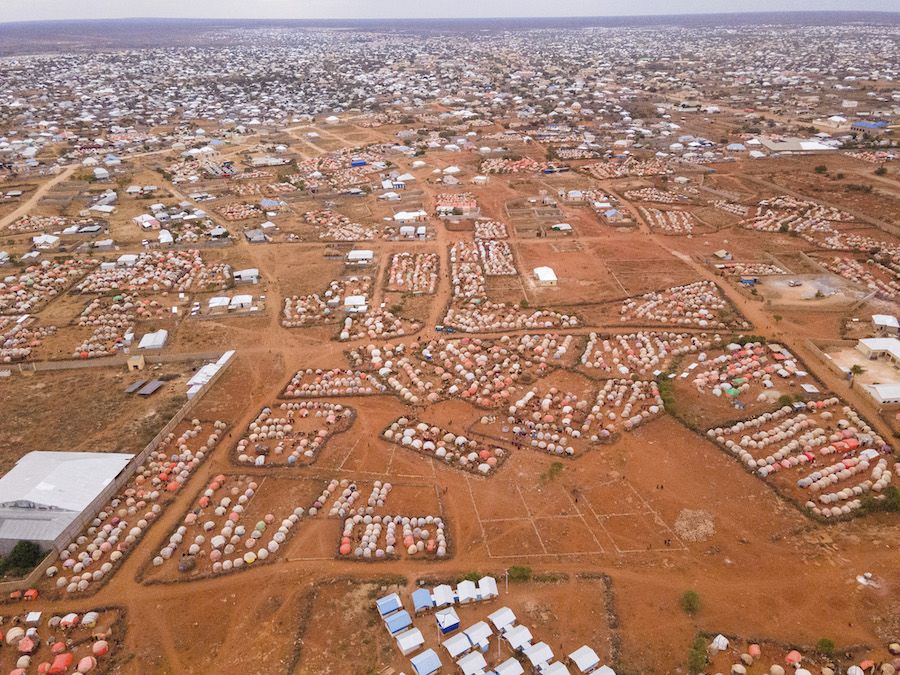

Aerial view of Barwaqo city extension in Baidoa. Foresight/ IOM 2022.

Aerial view of Barwaqo city extension in Baidoa. Foresight/ IOM 2022.

An IDP settlement in Baidoa that was at risk of eviction prior to the development of Barwaqo. Foresight/ IOM 2022.

An IDP settlement in Baidoa that was at risk of eviction prior to the development of Barwaqo. Foresight/ IOM 2022.

In 2018, the government of South West State generously allocated public land on the outskirts of Baidoa Town to provide more sustainable housing, land and property solutions for displaced families facing the highest risk of eviction.

The development of the land began in October 2018 through a partnership involving IOM, Danwadaag Durable Solutions Consortium, the Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster, humanitarian partners, and the Municipality of Baidoa.

By June 2019, the first 1,000 families were relocated to Barwaqo, where they gained improved access to a plot of land accompanied by a legally recognised land title and essential services. In February 2021, Phase 2 of the project successfully relocated an additional 1,009 families.

Since then, Barwaqo has been transformed into a city extension, providing access to basic services and livelihood opportunities through investments from multiple stakeholders.

The following video by IOM, the Danwadaag Consortium lead, offers an in-depth look at the process of developing and resettling IDPs in Barwaqo.

This 2019 interview with Abdullahi Watiin, Mayor of Baidoa, shows what government leadership on durable solutions looks like in practice.

Barwaqo exemplifies the potential impact achievable through a collaborative, multi-sectoral, integrated response, implemented by humanitarian, durable solutions, protection actors and the government.

Despite the success of the Barwaqo model, resettlement schemes located outside of cities are not always a feasible solution, particularly when implemented on a large scale. Such schemes pose implementation challenges and require significant time and resources.

For instance, the high costs to develop Barwaqo prove impractical when considering the needs of an estimated 3.8 million internally displaced persons. Additionally, the scarcity of available public land in urban areas often results in the allocation of remote and unsafe land by local authorities, which raises concerns on connectivity to urban centres and access to livelihoods.

Formalisation of land tenure agreements

To support integration and resilience of existing displacement sites in urban centres, Danwadaag has empowered local authorities in Mogadishu, Baidoa, Kismayo, Beletweyne, and Afgoye to establish formal land tenure agreements with private landholders. These agreements involve local authorities and humanitarian actors upgrading displacement sites through activities such as proper site planning, infrastructure improvements and provision of basic services such as water and housing. The improvements benefit displaced communities and increase the value of the land. In return, landowners agree to provide unused land to the displaced at no cost for varying periods, often ranging from three to seven years.

“This land was initially an inhabitable, bushy area. When I first let the displaced families reside on my land in Garasbaaley, I did it for charitable reasons. I thought about their well-being, knowing how difficult it is to live without access to land. I then decided to let them settle. Since then, it has become a modern settlement with shops that generate revenue through rent. The land value has gone up. And the area now has a borehole, which has generated extra income.”

A woman in a displacement site in Kismayo fetches water from a water point. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2021.

A woman in a displacement site in Kismayo fetches water from a water point. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2021.

The Consortium has also assisted local authorities in the development of standardised land tenure agreements that incorporate clauses that reduce the risks of common issues and the impact of mal-aligned incentives. One such provision addresses the issue of landowners seizing the personal property and shelters of the displaced after eviction. The agreement explicitly states that the displaced people can take their shelter structures with them if their agreements are terminated.

In cases where a landowner intends to reclaim their land, the occupants must be granted sufficient notice, typically 60 days, to facilitate their relocation.

A paralegal provides legal support and assistance to community members. Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC 2022.

A paralegal provides legal support and assistance to community members. Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC 2022.

"When I was displaced from Idow Liban village to Afgooye, we initially settled on open land. However, we were later evicted by the landowners, leading us to seek refuge at Albarako camp. Fortunately, the local authorities negotiated a three-year land tenure agreement for us, which has brought about a positive change in our lives. Prior to this agreement, we lived in fear of eviction, which prevented us from planning for the future or starting small businesses. Thanks to the training we received, we now understand our rights and have gained confidence. Anyone in the displacement site can start a small business without the fear of eviction."

A woman in a displacement site in Baidoa carries non-food items. IOM 2022.

A woman in a displacement site in Baidoa carries non-food items. IOM 2022.

The documentation of land tenure not only enhances the security of land rights for IDPs but also safeguards the investments made by development and humanitarian actors in vital infrastructure such as schools, information and community centres, water points, latrines, and markets.

"I have benefited from settling the internally displaced people on this land. Today, the telecommunication company Hormuud is putting up a mast in the area, which will improve the network. And a big market has come. All these benefits are a result of my decision to allow the displaced to settle on my land.”

The benefits and challenges of

community land purchases

Families who have purchased their land showcase their title deeds. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2021.

Families who have purchased their land showcase their title deeds. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2021.

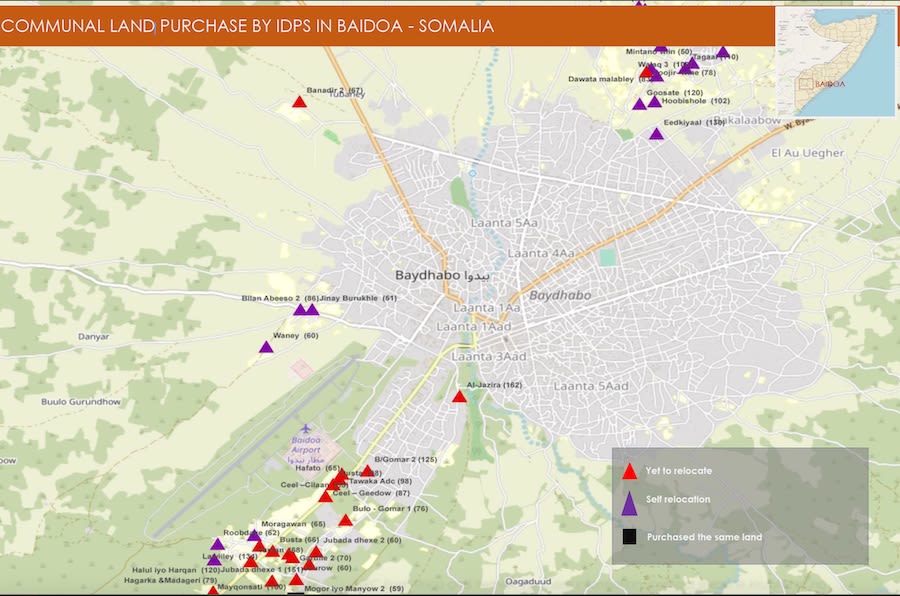

This mapping, conducted in 2021, identified 52 sites in Baidoa where the displaced bought land with communal contributions.

In some cases, displaced communities have pooled their own resources to purchase land. As part of a pilot project, Danwadaag supported 278 displaced families with the verification of the land transactions, relocation assistance, land tenure documentation, and access to water. Danwadaag also coordinated with other agencies to provide these families with livelihoods and housing support.

Watch the video below for more information on community land purchases.

Click on the site plans to learn more about the community decision-making in each site.

A woman who bought her land through a community land purchase showcases her title deed. Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC 2021.

A woman who bought her land through a community land purchase showcases her title deed. Abdulkadir Mohamed/NRC 2021.

While community-led land purchases demonstrate the resilience and self-reliance of displaced communities, including their ability to find their own solutions, this approach has its limitations. The resources available to displaced people is often constrained, leading to the purchase of smaller parcels of land than the standard minimum required, resulting in congestion. This can be exacerbated when other, non-owner families move in and contribute to further crowding and sprawling of unplanned settlements. Finally, limited funding for infrastructure development can hinder the construction of essential facilities such as schools, health centres, markets, and community centres, resulting in inadequate services for the communities.

Integrated rental subsidies

Under a unique project in Mogadishu, Danwadaag implemented an initiative that provided 100 displaced families with rental subsidies along with an integrated support package for a duration of 18 months. The integrated support package included subsistence and livelihoods assistance, information, specialised counselling, and legal assistance services to enable the displaced to exercise their HLP rights. The objective was to empower the displaced to gradually take responsibility for their tenancy once the project ended.

Khadijo stands in front of her market stall. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2021.

Khadijo stands in front of her market stall. Abdulkadir Mohamed/ NRC 2021.

Danwadaag also collaborated with the World Food Programme to provide an eight-month safety net to ensure a sustainable exit strategy for the families.

By promoting self-sufficiency and durable solutions, the project aimed to foster sustainable recovery that goes beyond temporary humanitarian aid.

In a review of the rental subsidy intervention, 96% of beneficiaries indicated that they would assume the responsibility for their rental obligations and other basic needs after the project.

Creating safe spaces for interaction and communication

Part of ensuring that Danwadaag’s housing, land and property interventions lead to sustained, durable solutions involves (re-)establishing relationships between rights holders—the displaced, refugee returnees and host community members—and duty bearers, including the state and municipal governments. In partnership with local authorities, the Consortium has organised various forums and dialogue sessions to improve communication between local authorities, landholders, and displaced populations, providing space for dispute resolution, mediation, and community interaction.

Community-led HLP dialogues in Mogadishu. Sunshine/NRC 2022.

Community-led HLP dialogues in Mogadishu. Sunshine/NRC 2022.

Farah's story

“Housing is not everything, but without it there is no life.”

54-year-old Farah is a father of seven and was an agro-pastoralist before he lost everything he had to the devastating drought in Somalia which prompted him to flee from his home in Lower Shabelle Region to a displacement camp in Mogadishu.

“When the river dried because of the drought, I lost my crops and the animals. We decided to move to the displacement camps in Mogadishu. We had nothing left—no animals, crops or even money.”

At the site, Farah participated in a Danwadaag-supported, community-led forum focused on dispute resolution and open discussion of challenges of housing, land and property, such as land disputes.

“I learned a lot from the forum. We discussed many problems that bring about conflict between landowners, the displaced and the host communities. We identified boundary conflicts between clans, as well as evictions by landowners as some of the challenges that the displaced face. I see a bright future for my family.”

Lessons learned

Securing land tenure is a key element in achieving durable solutions

It is increasingly clear that tackling insecure land tenure and preventing forced evictions are two of the most crucial and difficult steps in addressing the negative impacts of urbanisation, supporting urban displaced communities, and achieving sustainable solutions in Somalia.

Danwadaag has acquired valuable insights and knowledge in recent years through its involvement in various initiatives and the implementation of durable solutions interventions. One notable example is the government-led relocation project Barwaqo, which has shown some success and promise in benefiting small groups of displaced families. However, the implementation of such efforts presents challenges and gives rise to new concerns. Moreover, considering the substantial number of displaced individuals in the country, estimated at 3.8 million, these initiatives prove inadequate in terms of the resources required. Therefore, alternative approaches including communal tenure, rental interventions, and incremental and social housing are necessary to enhance tenure security. These measures would enable displaced families to remain within urban areas, granting them easier access to employment opportunities, essential services, and social networks.

Through an innovative project funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the consortium is adopting a new financing and testing approach. This project aims to bridge knowledge gaps, explore bold and novel ideas, and expand successful interventions. Taking a venture fund approach, the project will support initiatives that other durable solutions partners may hesitate or be unable to undertake, with the potential for significant long-term gains. Focus areas encompass land tenure, rental markets, water and housing models, and sustainable livelihood solutions.

Following its successful rental subsidy project described above, Danwadaag will assess both informal and formal rental markets in the two cities of Mogadishu and Kismayo. This analysis will play a crucial role in understanding the dynamics of the rental housing sector, informing policy decisions and supporting durable solutions interventions to improve access to safe, affordable, and adequate housing for displaced communities. In addition, Danwadaag will undertake a comprehensive incentive analysis across Baidoa, Mogadishu and Kismayo to identify and pilot more persuasive approaches for engaging key stakeholders in securing land tenure for displaced communities.

While multiple potential solutions exist, the Consortium’s experience emphasizes the significance of collaboration with government partners, communities, and private landowners. Integrating HLP across sectors is vital in generating durable solutions for displaced communities in Somalia.

For more information about Danwadaag's work in Somalia, contact Laura Bennison, Danwadaag Durable Solutions Consortium Coordinator.

Report designed and developed by Jenny Spencer at Untethered Impact.